My paternal grandfather was proudly given the name Seved Gustaf Lindorm Ribbing. He was born in 1862, the youngest son of Carl Christoffer Ribbing (1826-1899) and Emma Sofia Murray (1829-1891), at Ulfsnäs – an estate in the parish of Öggestorp (in Jönköping, Sweden) that had been given to governor Peder Svensson Ribbing 1574 by king Johan III.

Gustaf showed early signs of strong musical talent and started to play violin as a small child. Music and playing his instrument meant much to him throughout his life. For a period of time he thought of becoming a violinist and during his college years and even after he composed music for the violin and often arranged small concerts. He was somewhat of a daredevil also, being very keen on gymnastics and although he was tall he was unusually agile. During his childhood summers he and his cousin Sven Ribbing created small acrobatic acts and amusements which were performed at Riddersberg and Ulfnäs. Gustaf even learned how to walk a tight rope to boost the excitement.

His cousin Sven Ribbing later wrote about Gustaf and their summer activities. He revealed that Gustaf was ”richly gifted. He learnt to play the violin and over the years he reached a high level of proficiency while at the same time amassing a vast knowledge of music as an art form which came to be expressed in compositions and musical settings. He was a great learner which made him go through school with honors – and he was especially good at latin. Quick and witty and not without a poetic ear, the dreamy eyes, the black wavy hair and the tall stature lent him luck with the ladies, along with his romantic nature.”

Gustaf himself saw writing as a big gift and not one day passed without a written word. Thirty long letters remain today which he wrote to his parents between the time of his college graduation 1879 in Jönköping and the day he became Juridico Bachelor of Art in May 1881 in Uppsala, not having yet turned twenty.

Something happened Gustaf during the same year he started his study of philosophical literature, which made him turn towards the study of medicine instead. Exactly what happened is unclear, but a possible explanation can be found in a letter to his parents: a fellow student became gravely psychotic and Gustaf watched over him for a night and a day. He took it very hard to see his friend suffer and to realize the frustration that he could be of no help. Gustaf begun studying the Bible at that time, mulling over over complex existential and spiritual issues. He begun to turn away from the carefree student parties of the time which he had so enjoyed until this point. His entire outlook seemed to change.

Instead of choosing a prestigious profession, he was drawn to deeper concerns, a deeper calling, where he could be of real service to others – and that determination and drive to service was somewhat of a wilderness experience for a time. He pondered whether music or medicine would be his best way to serve God – and in the end he chose the path of medicine. His cousin Sven wrote that with every year Gustaf studied in Uppsala he became more and more introverted. Being a medical doctor satisfied Gustaf’s desire to improve the health and happiness of others, and he concentrated himself on this. Furthermore, he was a natural, naturally both cordial and kind, which enhanced his ability to treat people with their confidence in him lending them his guidance.

After 1881 his letters home became shorter and sporadic. His contact with his parents waned. There was a gulf between them that caused him distress and sorrow as they disapprove of him studying medicine. To be a doctor was not entirely accepted being young nobility at this time, it was rather considered the role of the commoner. As a result of their disapproval he was cut off and had to do without economic support from home to finance his studies. He had to rely on his own accord. Gustaf’s father was an atheist or at least anti-religious, which can have played a part in his lack of comprehension when it came to Gustaf’s spiritual tendencies and ruminations. In a short letter home by Christmas 1883 Gustaf wrote about being inspired by ”a very good and educational preaching that gave me a much needed awakening” and about his ”persistent concern and endless rather dour speculations that everything will end in uncertainty” and ”challenges and conflicts that paralyzes half of your powers”. It was clear that Gustaf had acquired a deep faith and sought God’s love but not without the cost of suffering, looming in the wake of surrender to life with this God, who is a mystery.

To his brother Bo, Gustaf wrote that he along with his studies worked from morning to late night every day of the week. He continued to write music, compose and give concerts as well as teaching music in Uppsala. This cultivation of beauty gave him much pleasure, and comfort, which he shared with others.

Around this time, during a temporary post as a music teacher at a girl’s school in Uppsala Gustaf met the love of his life. The handsome, gallant Gustaf was much admired and stimulated the interest of his students and they wondered if and when he would ever notice them and talk with them personally. Youthful crushes were not lost on him as he was a caring teacher. However, one day when Gustaf entered the class room his eyes fell on one girl in particular, and after a moment of silence he asked ”and what is your name, little girl?”. ”Elsa Nordling” she answered mildly.

This was in the Fall of 1886 and Elsa was only sixteen years old and Gustaf already twentyfour. He realized that she was far too young to be courted and waited until she turned seventeen later that same Fall.

Elsa was the daughter of Johan Teodor Nordling who was a professor in Semitic language and Sofia born Lindahl, an artist.

Elsa was religious as well and she and Gustaf found in each other a similar faith and belief in God. Both of them were influenced by the new evangelical revival movement sweeping the country, especially in Stockholm throughout the wealthy upper class that – among other things – dedicated themselves to atonement for the crimes of their high class towards the poor. They also had their passion for music in common as Elsa knew how to play the piano and according to Gustaf she had a nice voice for singing.

In his letter to his grandmother on his father’s side in April 1887 Gustaf gave a touching description of his beloved Elsa and their mutual love that was to flourish throughout their entire marriage.

Gustaf waited for his parents reply before the engagement was announced in 1888.

He wrote home: ”my beloved mother, I hope God both in the inner as well as the outer shall give me, the poor but by grace pardoned sinner, a pardon of grace and many blessings with Elsa.”

Elsa and Gustaf saw each other often in the Nordling residence in Uppsala, where he was always warmly welcomed. Not until he was finished with his studies, ten years later in 1896, did they get married in the Chapel of Ersta at Fjällgatan in Stockholm.

Gustaf’s mother Emma Sophia passed away in 1891 and his father in 1899. By this time Gustaf had become a medical doctor and eye specialist and the couple moved to Örebro where Gustaf opened an eye clinic.

My father Dag was born in 1898 in Örebro, followed by the birth of his sister Siv, two years later.

At that time Gustaf was deeply engaged with his concerns for the repercussions of alcohol abuse and often held talks about its detrimental effects. He was a member of The White Ribbon (Vita Bandet) along with his wife, who also becomes the first chairman of the local division in Örebro.

In May of 1900 a mission association was formed by bishop von Scheele which was called The Swedish Jerusalem Society (Svenska Jerusalemföreningen). The bishop had made a trip to the Holy Land during which he had visited both Jerusalem and Betlehem, and the distress, suffering and poverty had made a great impact on him. He created the Swedish Jerusalem Society to advocate for the health care and education of the struggling people, having a vision and resolve to establish a health clinic.

This help effort is now considered to be Sweden’s first humanitarian development project.

Gustaf was just finalizing his debt for his studies and had made a down payment for a summer house when he heard about this exciting establishment of the bishop’s medical charity and the opening of a clinic for which they needed a physician, and it was then that he was called by God, in his own reflections, to engage with this mission and its volunteers.

However, his decision was met with suspicion and skepticism from his family and friends. They had other plans for him and expectations, but Elsa, his devoted wife, gave him her complete support. She herself had a burning desire to visit and to work in the Holy Land.

In the beginning of the twentieth century Palestine was in submission to the Ottoman Empire. Therefore, the Turkish Government demanded a Turkish doctor’s degree, in French, to qualify for a license to legally practice medicine in Palestine. Undaunted, Gustaf decided that he would go to Paris to study French and work at French hospitals where he would prepare for the mandatory exam in Constantinople.

The move to Paris in the beginning of September 1903 was a big transition. Ester Carlsson who had been hired as a nurse at the doctor’s clinic in Örebro in 1897 accompanied the family but Matilda, who served as a maid in the family, remained in Sweden intending to marry. It was a hectic time and just prior to their departure little Dag broke his arm. This was painful, but not entirely unfortunate as the lively and sometimes unmanageable child kept calm and even subdued during the trip.

The arrival in Paris was quite shocking. The apartment in Paris had only two rooms and a kitchen and was dark, cold and filthy and the entire family fell ill. In the beginning of December they therefore determined to move to Marseille. It was from there Elsa and the children would be able to, with relative ease, make the trip to Palestine after Gustaf would pass the Turkish exam.

During all the years abroad Elsa wrote often and long letters to her mother and sister Tyra, full of vivid accounts and dramatic descriptions of the family’s every day life. Elsa had a keen sense of observation and so her letters were very rich, humorous and energetic (more than 120 hand written letters remain to this day). Elsa was a charming, sincere and magnetic person and made many good friends, whom she describes. Her letters were written from a warm female perspective and she displayed a great care and concern for everyone around her.

It was in January 3rd 1904 that Gustaf completed his studies and resolved to leave Marseille for Constantinople on a steam boat to take his exam. It was hard for him to say good bye to his ”remaining dear ones” as they saw him off departing from the harbor.

In a letter from that time he told his mother in law: ”I enclose a portrait of Elsa and the children that I took just before we said good bye in Marseille. It is also a moment that does not easily lend it self to description. One does not know what God’s plan is.”

Elsa worried over the children and in January 1904 she wrote: ”the dear children are indescribably disorderly for the moment, and especially Dag behaves as if he was not in his right mind! And at the same time as I long to create some kind of regular discipline I also dread the thought of making him behave on my own and in succeeding in creating some kind of order to all of this ”vitality”.”

The family awaited a sign from Gustaf to make the journey over the Mediterranean Sea to join him. And so in the beginning of February a message arrived: ”Passé. Gustave” to which Elsa replies ”Partions aujourd’hui.”

It was decided that the family would travel to Jaffa and to meet Gustaf there. The boat trip to Alexandria took three days and all four of them suffered sea sickness. They moved on from there to Port Said and then to Jaffa where no one was allowed to go ashore due to a cholera epidemic – and so the boat continued on to Beirut. Elsa had to pay fifty francs per person which drained her finances as the money Gustaf had sent for their journey had not reached them timely before they departed. Elsa installed herself, the children and Tilda – who had now joined them as her marriage never took place – in a hotel room to wait for Gustaf, hoping he would find them.

February 15 Elsa wrote in a letter to her parents: ”Praise the Lord! We have found each other!” Gustaf had been delayed in Constantinople as he did not receive his diploma in time. He wrote to his mother in law: ”it was an indescribable moment to find them all healthy and sound at a hotel. Little Dag, the sensitive one, started to cry uncontrollably with joy.”

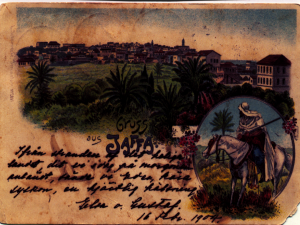

The day afterward, they travelled to Jaffa and on to Jerusalem. One week later they arrived in Betlehem.

Upon arrival Elsa wrote: ”From the shore of the Holy Land, where we this morning arrived, we send you our beloved brothers and sisters, our dearest regards. Elsa o Gustaf 16 febr. 1904.”

Upon arrival Elsa wrote: ”From the shore of the Holy Land, where we this morning arrived, we send you our beloved brothers and sisters, our dearest regards. Elsa o Gustaf 16 febr. 1904.”

Gustaf wrote continuously to the Swedish Jerusalem Society, chronicling his journey from Sweden, his time in Paris, throughout his studies, his final examination in Constantinople and his arrival in Palestine. From Betlehem he wrote comprehensively about his experiences: treatments, surgeries and the numerous house calls that he made. He recounted his meetings with several patients which often he found full of prejudice and narrow mindedness but he also made it clear that they at the same time were full of good will and warm love. Christians, Jews and Muslims were all treated in the same way.

Gustaf also told about his family and their everyday concerns, about his new friends and unique trips to sites in the area that he visited. He gave detailed accounts regarding their economical situation to the board of the Society throughout all of his years in Palestine. These letters were all published in the Swedish Jerusalem Society’s magazine between 1903 and 1914.

Around the year 1900 eighty percent of the population belonged to different Christian denominations, the remaining twenty were avowed Muslims.

The readjustment of Gustaf’s family to the new everyday life in Palestine was a huge challenge of cultural shock. The idealized pictures they had painted of the Holy Land quickly disappeared, dreams of ”the land of milk and honey with rolling meadows, paradise orchards and fruit bearing trees by rippling streams with shepherds watching over their herds.” In truth, what they saw, was compared to the familiarity of their lives back home: the nature of Sweden, the climate, accommodations, availability of food – and Elsa noted: ”the price of figs is less than of potatoes.” They arrived in the winter time, the landscape was grey and dry, and the houses built of stone were cold and damp. Elsa especially got homesick.

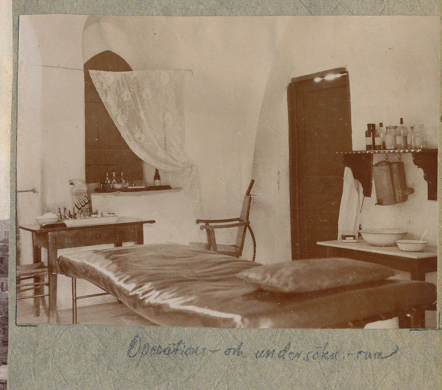

A time of endless difficulties with unfamiliar and primitive circumstances began to take its toll. Gustaf immediately developed a clinic and a pharmacy at the ground floor of their rented house in Betlehem and Elsa rearranged the floor upstairs as well as she was able to. It was challenging but she resolved to conquer all obstacles. In this battle, she began an all out assault to exterminate vermin and filth, scrubbing and painting the walls and floors and washing the windows of their modest apartment, making it inhabitable.

The rumor about the new doctor spread fast through Betlehem and the sick as well as their families turned up at all hours of the day and night. Within only a a few days after their arrival Gustaf had taken on the treatment of some ten hard cases.

The rumor about the new doctor spread fast through Betlehem and the sick as well as their families turned up at all hours of the day and night. Within only a a few days after their arrival Gustaf had taken on the treatment of some ten hard cases.

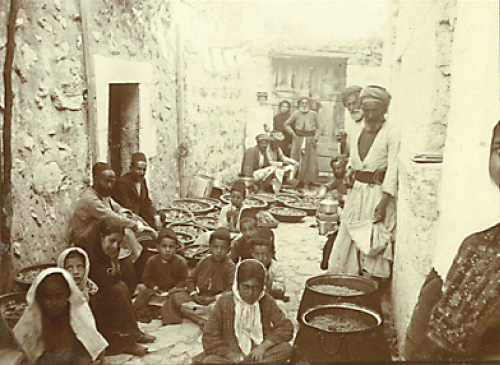

Fortunately, their house was well situated in the Western part of town near an olive grove in a lovely valley. The main country road between Hebron and Jerusalem was busy with traffic and even before dawn, large crowds of loud locals would gather outside the door of the waiting room on the ground floor to be granted an appointment with the doctor. Elsa wrote in a letter: ”the large crowd of patients has – hours on end – like a long motley ribbon wound itself through the the clinic’s different rooms. The women wearing long white head scarves and more or less richly embroidered gowns, children and men in colored frocks and fezes, Bedouins in coarse wide striped cloaks and twisted multi colored turbans, anxiously describing their various symptoms by the help of the young interpreter … the high ceilinged and arched rooms, with their three feet thick walls avidly picks up and reverberates with a jumble of voices and outcries in Arabic, Swedish, French and German.”

The language barrier Gustaf encountered was a great challenge for him in his work. He did not understand Arabic and was hoping he would soon learn to communicate quickly but he did not have the time to do so due to the enormous demand on his time for the treatment of illnesses and injuries. A translator was immediately hired.

Despite the difficulties, Gustaf’s practice grew exponentially and within seven months in 1904 he had treated 1,360 patients, conducted 122 surgeries and made 555 house calls throughout Betlehem. The conditions within the small clinic were extremely difficult with the lack of space being very pressing. Some of the patients had to be placed on the floor or even lodged in the dusty cellar between packing cases. Gustaf suggested in one of his letters to the Society perhaps that they should rent a little house for a while, to be used as a small hospital annex.

In May 1904 he wrote: ”Regarding the resources of the Society I can’t emphasize enough the benefit of having a hospital – even if only a small one. The difficulties without such are felt daily.”

The infirmary and most of the houses in town were leaky and dusty with only small openings for windows and the poor lightning especially made the many eye surgeries extremely hard to perform. Due to shortage of space many patients had to be cared for in their own homes which posed an increased risk of serious infections. It was also very time consuming for Gustaf and Else to have to make house calls.

Nevertheless, Gustaf found time to lead a short morning prayer at the clinic before it opened and he spoke when possible with the patients about his deep faith and his trust in God. He chronicled his long and tiring hours and the frustration that he did not have time to further his studies, nor for necessary correspondence or for time with his own family. He came down with a throat infection while his two lively children attracted dysentery.

The three of them soon recovered and they all began to assimilate with the culture where they had been called.

One day, the whole family was invited to visit a vine yard in Betlehem and upon their return in the evening while approaching their house little Siv shouted with joy ”Soon we will be home!” Elsa was very touched by her words and wrote: ”I feel that we – praise the Lord – are beginning to put down roots in the new soil and that we also are blessed with the happiness of having a home and all of what that brings with it.”

Gustaf wrote about a Bedouin couple coming to the clinic with their two year old son, who was dying from difficulties in breathing. He described the anguished father, in dirty clothing, holding in his arms a half dead child who was turning blue. Gustaf immediately dilated the boy’s throat and inserted a silver tube, despite the parent’s frightened protests. With this quick action, the child regained his color and his consciousness, and was saved.

The boy was a unruly child and among other things threw stones at his parents without them disciplining him. When the boy misbehaved towards the clinic staff they slapped his little fingers. ”As fed up we have been with the boy we have not been able to avoid having tender feelings towards him as well”, wrote doctor Ribbing. ”and we have already been rewarded through our little patient… we have been met with appreciation and recognition from the Bedouins. The result being that now many of them have come from the desert just to see this child of whom they have heard so much good news, that he had been saved from the grave by having a hole made in his throat.”

They were befriended by the Bedouins then and later in November the doctor and his family were invited to visit the Bedouin camp. Gustaf, Elsa, Siv, Dag, Ester and Tilda rode horses to the gathering, to the joyous welcome.

In April 1905 Elsa gave birth to a boy who was named Bo, but since he was born in Betlehem and therefore considered to be a Betlehemian he came to go by the name of Boas. Gustaf wrote to his mother in law that Elsa was prettier and happier than ever. Boas was a special delight to her and he became her favorite child.

The family labored on but it was Fall until they were able to buy their first sickbed. Finally the patients could rest comfortably and recover following complicated surgeries.

There was one little Arabic girl from the neighborhood named Hanna, who had come been infected with tuberculosis in her hip. Gustaf performed a very difficult surgery and Elsa assisted. It was unbearable for Gustaf to see this small and very sick girl, laying on the hard stone floor with only a very thin mattress beneath her. He considered sending her to a hospital in Jerusalem, which would have been a painful journey, but decided instead to send to buy a small sickbed with an elastic bedside. Hanna was overjoyed and for a moment forgot to be sad and kissed the doctor’s hand in gratitude.

Gustaf was succeeding to bring not only healing but confidence to his community, in his sincere care for them.

Treating this unique local population with the very same methods that Gustaf had been taught in Sweden was difficult to say the least. Many times he was met with skepticism and the giving birth to a child for one thing was a situation when it was against customs and traditions to have a male person present. Despite that he was summoned when life threatening complications arose and he recalled one of these instances, a breech birth, when the women hit and cursed him and tried to force him out of the room. When he was able to save the child, however, the atmosphere shifted and they overwhelmed him with their appreciation and blessings.

Gustaf was unable to hide his pride when they gave the new born the name ”Costa” after him – the Betlehemians called my grandfather ”Hakim Costa” which means doctor Gustaf.

In a German annual report from 1905 one could read: ”there is probably nowhere on earth where mission work is more challenging than in the Holy Land, especially in Betlehem. The amount of people seeking help at the Swedish doctor Ribbing’s clinic has risen to the point where building a hospital seems to be unavoidable.”

During October alone, Gustaf had approximately one hundred patients who visited the clinic.

Sadly, throughout 1905 the family themselves, Ester, Tilda and especially the children suffered many illnesses. Besides the continually and reoccurring problems with their stomachs, with fever, vomiting and diarrhea, Dag and Siv both came down with the measles and the day after Gustaf and Else took off for a two week vacation in Haifa, Dag got sick with cholera which he almost did not survive. Later Dag explained: ”I did not want to die when mother and father were away.” Boas got sick with malaria later in the Fall the same year.

To facilitate Gustaf’s house calls around the area they bought a donkey who was given the name Sverre. I can see before my inner eye how my grand father, being a tall man, rode the donkey with his doctor’s bag and the long legs dragging in the dirty ground. The children were overjoyed.

By new years the family had bought an organ that Elsa played and sang along with. According to Gustaf she was good at the organ and had a fine voice. He himself played the violin.

In a letter penned to his mother in law on New Years Eve 1905, Gustaf wrote: ”The annoying children! But how they interest you. Today I have played all day with Dag and Siv and they have in return been behaving so well I am touched.”

The family was hoping to move in the beginning of 1906 to another house that would be their private home and so that their current lodging could be made into a small hospital. But the landlord of the new house had a sudden change of mind to everybody’s disappointment.

On a brief holiday on a vine yard in the cool mountains in the summer of 1906, the family was disrupted by Boas contracting a a nerve fever. Elsa and Boas were seated on a donkey led by Gustaf back down to their house in a stuffy Betlehem. After a week of medication an energetic water treatment was initiated and Boas recovered within six weeks time just before they have lost all faith.

The following episode was given the title ”The valley of the shadow of death” by Gustaf:

In November 1906, the family was stricken with grief when Gustaf caught pneumonia after an emergency house call. That same night he began shaking from severe fits of shivering and the morning after he spat blood. His heart showed serious signs of exhaustion and the catholic doctor who came to see him found his condition so critical that one Arabic doctor and two physicians from the German hospital in Jerusalem were sent for. Only a few days later Elsa went into labor and gave birth three weeks prematurely to a little baby girl. They gave her the name Dorkas.

Gustaf’s illness became unusually severe and protracted, with much pain, and did not turn around until the twelfth night. He kept his faith throughout and resolved to see the illness as a test and blessing from God. Else wrote to the Society: ”Like always, the bigger the need the closer is God, and we have, despite the indescribable suspense and worry, kept our hearts serene in the depth of our souls. God has also granted us proof of loving sympathy from all sorts of countries and people, protestants, greeks and catholics – everybody has come together in their feelings during this time. It has been touching to hear how they in Betlehem as well as in Beidjala and Beitsahur have suffered with us. With the impetuous emotionality of the arabs, they have one after the other, been tearing their clothes and not been able to eat or sleep for days on end.”

Everybody who had shown empathy and compassion during the time Gustaf was sick was later invited to a ”poor man’s party”.

At the same time it came about that Siv attracted tonsillitis and otitis and Dag came down with smallpox. Gustaf wrote: ”so we then had the feared guest in our house.” Dag and Ester were immediately isolated on the ground floor but the pustules turned out to be of the milder kind and Dag’s face was almost completely spared. Thirteen days later all the children had rashes but luckily they too were minor. Thankfully all in the household were vaccinated besides Dorkas.

Gustaf recovered slowly after the long and severe illness. At first he was unable to walk, but he regarded the rehabilitation period in his home as a privilege and noted: ”No one is allowed to disturb my happiness with my family. From morning to night I am left alone with my wife and my children and can follow them in work and play in complete harmony and peace.”

After some time of recovering Gustaf took off to Jaffa for a month’s vacation by the sea away from the cold winter of Betlehem and from there he wrote: ”By the grace of God’s goodness and power, my health and strength are returning and whatever is left of the disease is fleeing from the lungs due to the warmth, sunlight and fresh air.”

In May 1907 a letter arrived to Elsa’s mother and sister Tora: ”Beloveds! Today at about seven o’clock in the morning our little sweet darling Dorkas was called home to God after only three days of illness. Tomorrow when the sun rises we will put down her remains in the protestant cemetery in Betlehem. We choose the early hour to be reasonably undisturbed following her to her last resting place. The Lord gave and the Lord took, praise the Lord. In mourning, your Elsa.”

Dag was at this time attending a German school in Jerusalem since a year back and was there housed by Dr. Einsler during the weeks. Siv attended an English-Arabic school and was learning Arabic. Her teachers were very pleased with her and surprised by how fast she picked up speaking the language. ”Imagine”, Elsa wrote home, ”if father had known that his grand daughter would be speaking like an Arab.”

One special patient Gustaf wrote about in 1907 was Hassan, an orphaned fourteen year old boy from the Valley of Jordan who had come to the nursing home ill with trachoma, a very usual disease around this time in Palestine. After treatment the boy remained with the family and Gustaf was impressed by Hassan’s simple habits. He wrote: ”What do you know, it’s all that is needed.”. In a letter to the Jerusalem Society he wrote of discussions of religion, which he had with Hassan. Gustaf pondered how he could get the patients to come into contact with God and how he could convince them of the benefits of prayer and to make them understand that the spiritual life perishes without.

He wrestled often with his own prejudices. ”Do not judge”, he wrote and was speaking to himself.

Both Ester and Tilda were included in the family and they all sometimes payed visits to the Swedish-American colony in Jerusalem, to where the ”Dala-people” from Nås in Sweden had immigrated. Gustaf did not understand the strict religious atmosphere and rules they enforced – he, who was very fond of his family, could not see why men and women were not allowed to mix socially. Even when they were a married couple it was forbidden. They were denied a full life with their whole family, and it was a point of frustration for him he could not reconcile.

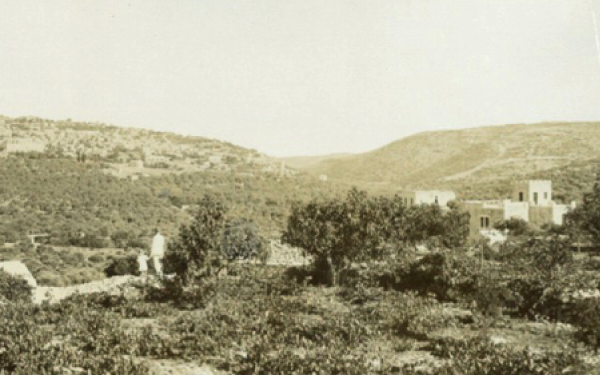

However, the urgent need for a hospital was Gustaf’s greatest concern. To realize this dream he constantly made calculations which in detail specified all costs for a doctor’s residence. He presented the proposal to the board which in 1907 approved the purchase of a property meant to establish a house for the family in Beitdjala. The property was very close to the Betlehem city limit. In those days it had a fantastic open panoramic view over Beitdjala’s olive groves. Today there is no remnant left to visit as buildings and the wall that Israel has built obstructs the view of the beauty.

The first cornerstone of the house was laid down on August 22, 1907, and on December 8 the ground floor was completed. The family moved into a temporary house during the construction while the old home was remodeled into a nursing home. Much of Gustaf’s time was spent managing the construction work and he himself made the majority of the drawings for both their private home and the nursing home.

Despite Gustaf’s illness and lengthy convalescence during this time, there remains a record of 1,887 treatments conducted, of which 146 were surgeries and 86 house calls, at the clinic and in the private home, 1907.

In the beginning of 1908 another baby was born, a boy who was given the name Hans Lennart. Elsa did not have enough milk for the new born and as it was hard to find milk replacement, a wet nurse was hired. She was unable to tell time from a clock and therefor Elsa hung a red blanket out the window to call on her when she was needed. Hans Lennart had four bouts of malaria during his first year. Elsa was strained and a woman named Hilma Andersson was sent for from Sweden in the Spring to help. She wrote later to the Society: ”I almost feel like a member in the doctor’s loving family”

The construction of the new home took time as material did not arrive when expected and the work progressed slowly. On top of that there was substantial hassle with the Turkish authorities regarding permissions, prices and fees. Gustaf described at large to the board all the problems he encountered and he asked to be released from the accounting. He also suggested a local doctor to be hired so that he himself can direct his time to the more complicated cases and the surgeries.

Dag still attended the German school and Siv an English school for arabic female teachers in Betlehem. She would leave every morning just before eight, have dinner at the school and then return home at five. In the beginning some children tried to threaten her, wanting to take her books and money and the boys wanting to kiss her but after Gustaf walked with her one day and gave the children troubling Siv a lecture, they left her alone.

Gustaf’s work examining the sick, giving them advice and medicine was not highly rated by the patients. It was not until he performed surgery that they began to respect him a bit more. He coped with many challenges. The most usual eye affliction he struggle with was the tough disease trachoma.

In 1908 he performed 173 surgeries, took care of 88 patients at the nursing home and made 1,888 treatments all in all.

When Siv matriculated to attend the German school in Jerusalem in the Fall, the family rented two small rooms for the children in the city. Elsa and Tilde took turns living there with them every other week. Boas had a severe concussion when he fell down a high stair case and Dag came down with rheumatic fever.

Towards the end of the year Ester returned to Sweden and just before Christmas the family finally moved into the private, although not yet entirely finished, residence.

In a long letter to the Jerusalem Society in July 1909 Gustaf recalled how a usual Monday would look like in Betlehem, as a schedule, from early morning, late into night. Here is an episode:

One Monday morning the older children were about to ride on Sverre to the German school in Jerusalem. Gustaf lifted Siv up onto the pillow behind the saddle where Dag was already sitting and so off they went, up the slope towards the main road. After ten minutes they returned and with tears of frustration they shouted ”Sverre absolutely refuses to go to Jerusalem, he just walks in circles and bruises our legs against the edgy wall! We are hitting him as much as we can, but he doesn’t care! We will be late for school!”

Gustaf took the whip and gave the animal a couple of strikes. The donkey started to walk reluctantly but tried a few more times to turn around. Gustaf followed them a bit on their way and not until they pass the place where Dorkas was buried, did Sverre start to move a bit more steadily forward. When Saturday came and the children rode him back home he ran as fast as he could to his cosy stable.

When the family once again was afflicted with malaria Elsa travelled to Sweden in August during the children’s summer recess. Gustaf made a journey for the purpose of study and recovery and brought Dag with him. Before he left he finished a sketch for a Swedish hospital adjacent to the doctor’s residence in Betlehem, that he turned over to an architect to make a drawing from.

In 1909 the number of patients rose to 2,580 of which 223 were surgeries and 262 house calls.

During 1910 Gustaf was constantly busy with his work despite his poor health and the clinic and the nursing home was constantly filled with rowdy and many times very tiring – but yet, according to Gustaf – ’so dear’ Arabs.

During the whole of March and through July the members of the family took turns being sick. Siv had malaria. Elsa underwent a surgery and another one after suppuration and fever. Farrah, their translator and right-hand man, had surgery. Hans Lennart had dysentery. Siv got tonsillitis and an earache. Gustaf, Elsa and Dag got malaria and Gustaf developed a serious pus infection in his leg. Two of the nurses fell ill with gastric catarrh and jaundice, Hans Lennart came down with malaria and Elsa had diarrhea and fever. After that Hans Lennart developed a severe eye infection and Dag and Siv contract the flu with high fever and then it was Boas turn with the malaria. All of these illnesses were hard on everybody in the household.

In October Gustaf wrote that the nursing home was overfull and he found it hard not being able to house more patients. ”The clinic and the nursing home is full of activity. The sick are laying in beds and windows, on benches and floors, and despite the room being tight we have a compilation of trachoma, glaucoma, tuberculosis in lungs, legs and glands, dysentery and hernia.”

The religious work on the other hand, was being organized in a more satisfying manner: an Arabic woman was hired to be in charge of devotional service and to speak with the female patients. The two local pastors also held regular services.

Towards the end of 1910 a quotation was made ready for the hospital by Gustaf for 47 beds and a water tank, but the Society did not yet have funds.

Elsa was still staying every other week in Jerusalem which provided her with well needed change and more of a social life than she had in Betlehem. In Jerusalem at this time there were all kinds of groups and societies promoting a sober life that she often attends: YMCA, YWCA and The White Ribbon.

In April 1911 Gustaf took his wife, Dag and Siv, Tilda and Farrah and some of the other employees on a vacation on the horse Snow White and a couple of donkeys. They wanted to see the Dead Sea and the River of Jordan before they left for Sweden for a one year vacation.

”October 21, early in the morning, when the sun cast its, in the East so fleeting and rose colored, light laid on the mountains and houses of Betdjala with its never-to-be-forgotten olive valley by its foot, we said good bye to our Swedish and closest Arabic and German friends by the main road to Jerusalem” – was how Gustaf describes the departure from Palestine.

Elsa fell ill and was sick throughout the trip back to Sweden and Gustaf had the impression that she would never return to Palestine, regardless of how much she loved the sun and warm climate of their new home. ”And what will then become of me?”, he wrote.

In fact, neither Elsa, Dag, Siv nor Boas would ever return to their home in Palestine.

Once back in Sweden they decide to make a home of a small apartment in Uppsala. Elsa was bedridden for a while but soon recovered.

1912 was to be a sabbatical year for Gustaf but instead he accepted a position in a hospital in Kristianstad to better his surgical skills. Two new nurses and a female pharmacist was employed by the board of the Society for the work in Betlehem and together with Gustaf they searched for someone to replace him at the clinic – but without success. They were forced to take the difficult decision that Gustaf would return, leaving Elsa and the children in Sweden. Gustaf could not imagine himself without the family but comforted himself in having Tilda and little Hans Lennart accompanying him to Palestine.

In early February 1913 Gustaf, Tilda and Hans Lennart journeyed back to the Holy Land. Gustaf noted that there were many Austrian soldiers on the train and he drew the conclusion that their army was preparing for war.

When he arrived back in Betlehem Gustaf was received by all of his friends and felt encouraged in his solitude by having been welcomed by both Germans and Brits as well as the Arab community he knew so well. The cornerstone to the hospital was finally laid in November 6, 1913. ”Our very own hospital on Swedish ground”, Gustaf wrote about the occasion in a letter. ”May it be God’s will the the work will be fulfilled.”

The cornerstone to the hospital was finally laid in November 6, 1913. ”Our very own hospital on Swedish ground”, Gustaf wrote about the occasion in a letter. ”May it be God’s will the the work will be fulfilled.”

Many came to Betlehem to celebrate. The Pascha of Jerusalem, the mudir, the city’s mayor, the Swedish general consul, the German general consul and a representative for the Osmanian Empire’s government, along with many from the American colony, the British pastor and the Arabic pastor and many Palestinians, peasant and Beduoins, Turkish soldiers and more.

Many came to Betlehem to celebrate. The Pascha of Jerusalem, the mudir, the city’s mayor, the Swedish general consul, the German general consul and a representative for the Osmanian Empire’s government, along with many from the American colony, the British pastor and the Arabic pastor and many Palestinians, peasant and Beduoins, Turkish soldiers and more.

During this time, Gustaf made a short visit to Sweden in the Summer of 1914. On August 1, he departed and travelled to Malmö to take a boat via France and Egypt in an attempt to return to Palestine. He wrote to Tilda who remained in Betlehem with Hans Lennart: ”So, here I am in Malmö. A few days ago I took a heartbreaking farewell of my beloveds and since then the awful war have blocked me in all ways both through and around Europe. It came down like a lightening. Yesterday when service begun in Malmö all the bells in the city started to toll and did so for three hours – to bring Swedish men to arms! (Though only to defend our neutrality). With a tender heart I am thinking of you and little dear Hans.” .

He had to stay in Sweden.

Left behind in the ”land of the sun” was Gustaf’s sunshine Hans Lennart and Tilda, his edifice, his garden, his patients and his friends. Tilda and Hans had to flee, during difficult circumstances out of Palestine to Egypt where they managed to get on a boat across the Mediterranean.

Left behind in the ”land of the sun” was Gustaf’s sunshine Hans Lennart and Tilda, his edifice, his garden, his patients and his friends. Tilda and Hans had to flee, during difficult circumstances out of Palestine to Egypt where they managed to get on a boat across the Mediterranean.

Gustaf, who was then working at the hospital i Örnsköldsvik, received a phone call late one night and heard a child’s voice saying ”Hello father”. Gustaf asked if it was Hans. ”Yes, we came with the boat and it rocked terribly.” There had been a storm on the Baltic during the passage. They had made it home.

The family was now gathered in Sweden. Gustaf’s intention was to wait until the war was over and then go back to Palestine. But the years passed and they began a plan to stay permanently. The family moved to Halmstad where Gustaf opened his own practice and built them a house.

The Spanish flu at that time was running rampant and Gustaf was working hard to treat its victims.

By the beginning of October the family moved into the new house. Elsa later recalled in a letter to Tilda how Gustaf came home late the same evening and was happy as a child over their new home and the little garden in which they could now plant and sow. However, the day after – on October 11, 1918 – Gustaf fell sick and three days later he died, of the Spanish flu.

The war ended one month later, on November 11, the same day Elsa turned 48. She was now alone with the four children. Dag was twenty years of age and studying at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. Siv was eighteen and had a position as a secretary at an insurance company. The younger boys were still in school.

Elsa was forced to sell their house in Halmstad due to the huge loans that had been taken for its construction, and there was no savings left. She eventually moved back to the town of Uppsala where she was born and grew up. Then, in 1927, her beloved Boas died.

All of this tragedy and loss made Elsa wonder why God was so hard on her and after all of her years of faith she began to doubt the Lord God’s love.

In the last year of her life Elsa moved in with my parents at Mosebacketorg in Stockholm. Sometimes she sat by an open window playing the organ and singing religious songs – something which was disturbing to her son, my grandfather Dag, who had become an atheist.

In the early morning of Februari 27, 1931 Elsa died peacefully in her sleep, 61 years of age.

The hospital in Beitdjala that Gustaf founded was not completed until 1922. The private home and the hospital are incorporated and the entire structure is in use as a hospital that today goes by the name KING HUSSEIN IBN THALAL HOSPITAL. It is still owned by the Swedish Jerusalem Society, situated on land occupied by Israel and run by the Palestinian Health Authorities. The Society is responsible for its maintenance and expansion and is largely in need of economical support in the form of financial aid and gifts.

On October 30, 2001 the hospital was hit by an Israeli rocket that destroyed among other things the entire maternity ward. After this incident the hospital had to be entirely renovated and reconstructed, made possible largely with aid from SIDA – the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

It was rededicated in 2005.

Gustaf’s nursing home, once so small and humble, is now a major regional hospital, mainly meant for the local Palestinian population in the area.

My grandfather is still a legend in Betlehem. He is remembered as the tall doctor Gustaf – ”Hakim Costa”.

Maria Ribbing

The text is edited and translated by Kajsa Ribbing